DIVA - An intentionally vulnerable Android app - Part 1: Insecure Storage

by purpl3f0x

Intro

After spending a year working on Android malware analysis, I am now making the transition to Android security assessments. I’ve been studying up on the subject for the last few weeks, and I have been practicing on deliberately vulnerable apps. I am going to share my experience working with DIVA, the Damn Insecure and Vulnerable App. Each of the challenges are fairly short, so I’ll be breaking them up by category instead of doing individual posts.

Today, I’ll be covering the challenges that fall under the umbrella of Insecure Storage. There are four challenges in this category, each slightly increasing in difficulty, but each also teaching the different places that should be checked when assessing an Android app.

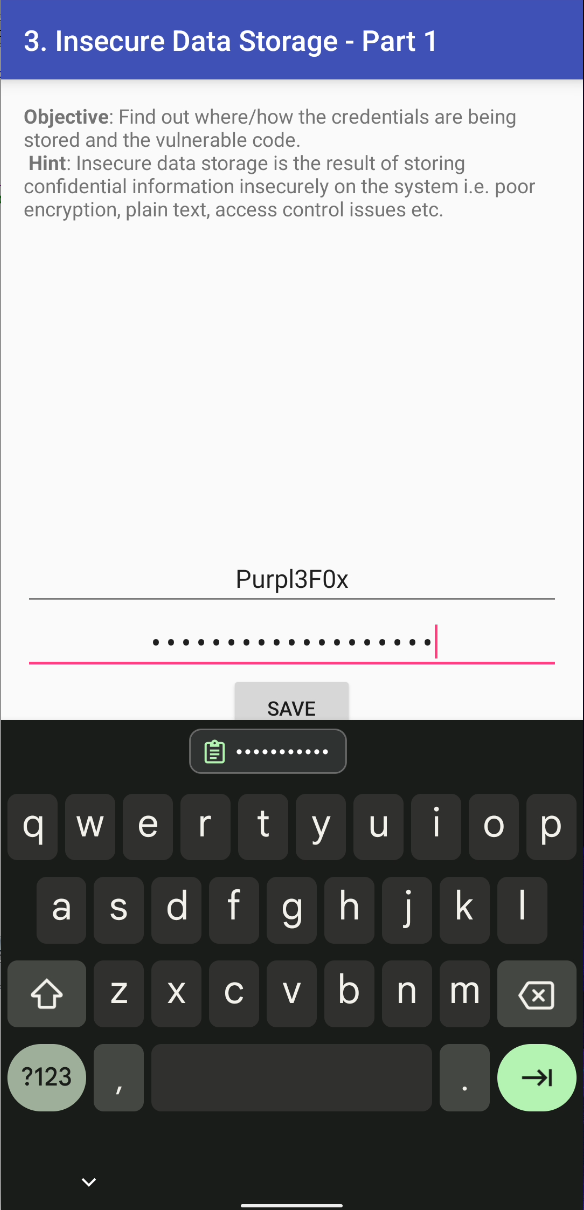

Insecure Storage 1

The challenge asks you to enter a username and a password, and it will store it somewhere in an insecure manner. The goal is to see if you can find where the credentials were stored, and prove that they were stored in a way that goes against best security practices.

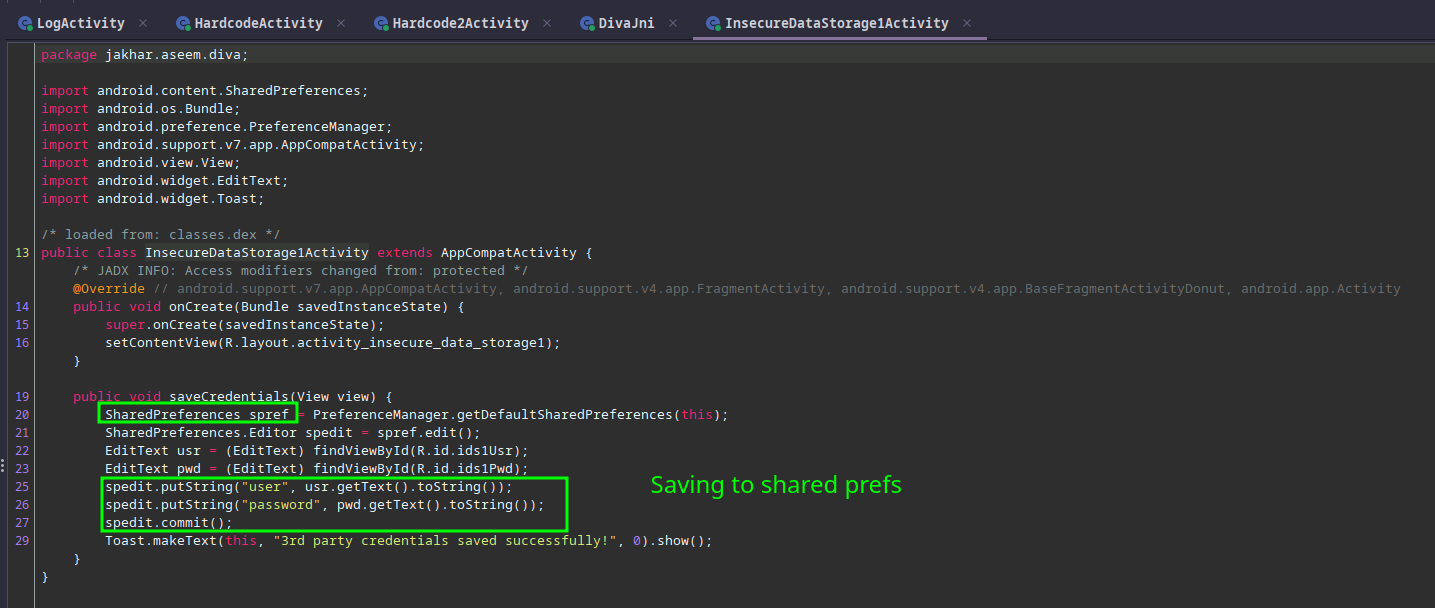

To get our first clue on where to look, we can check out the decompiled code in Jadx GUI:

It appears that the credentials are being put into the Shared Preferences on the device, and it doesn’t appear to hash or encrypt the credentials based on what is in code here.

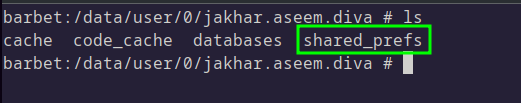

Using ADB, we can connect to the phone and have a look in the files:

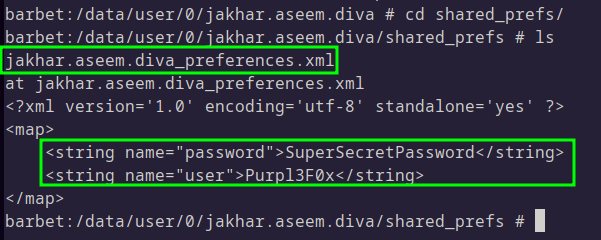

Inside this directory is an XML file. We can use cat to view the contents of the file and see that the credentials were stored in plain text:

This solves challenge #1.

Insecure Storage 2

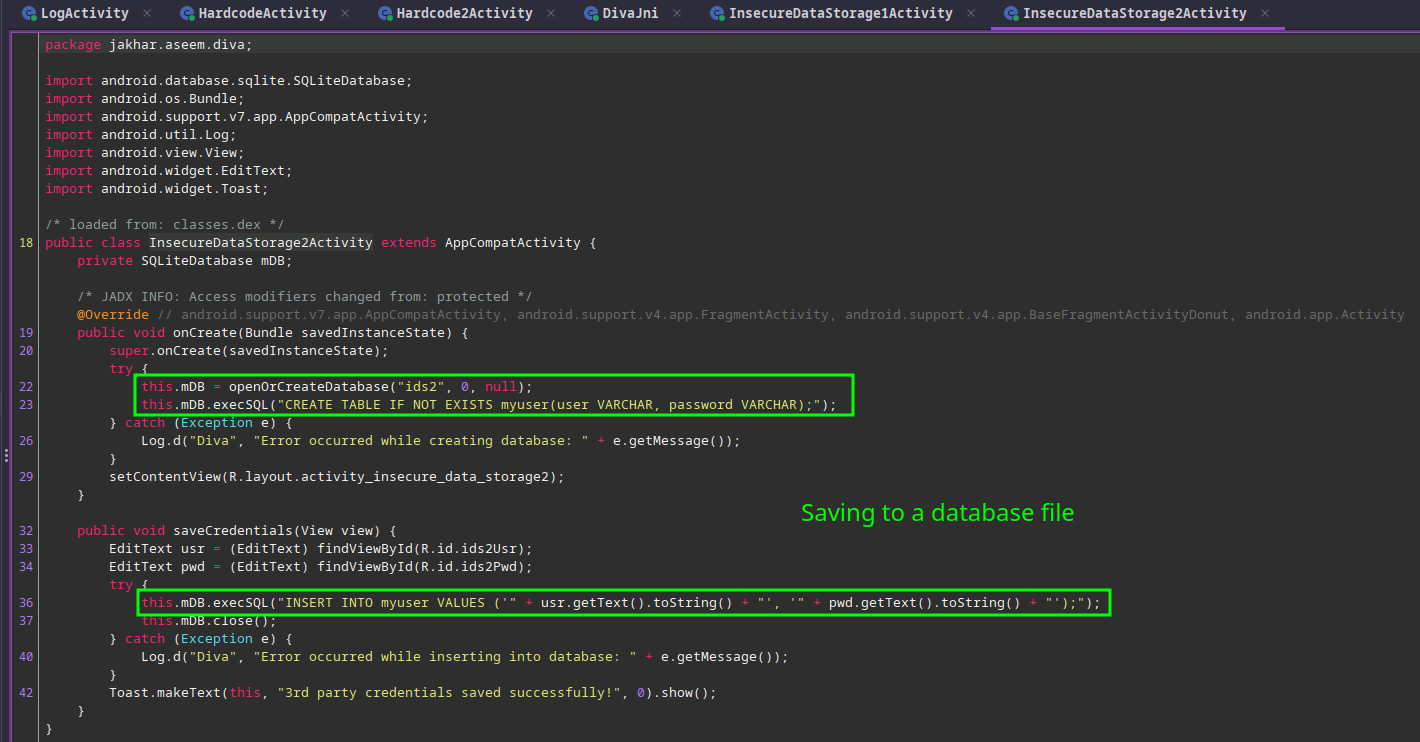

Challenge #2 asks us to input credentials again, but this time they will be stored a different way. Once again, we look at code to get our hint:

Android apps can make use of SQLite for storing and querying data, and it appears that in this case, the credentials we supplied are being stored in a database by the name of ids2. Once again, there is no evidence in code that any hashing or encryption is happening.

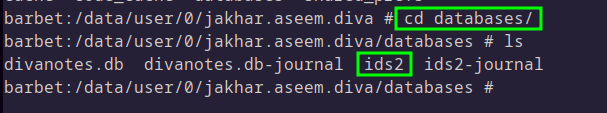

Making use of the same ADB shell, we can see where the database is stored:

To make it easier to work with the file, we can copy this file to the sdcard, and then use ADB to pull the file to the local machine:

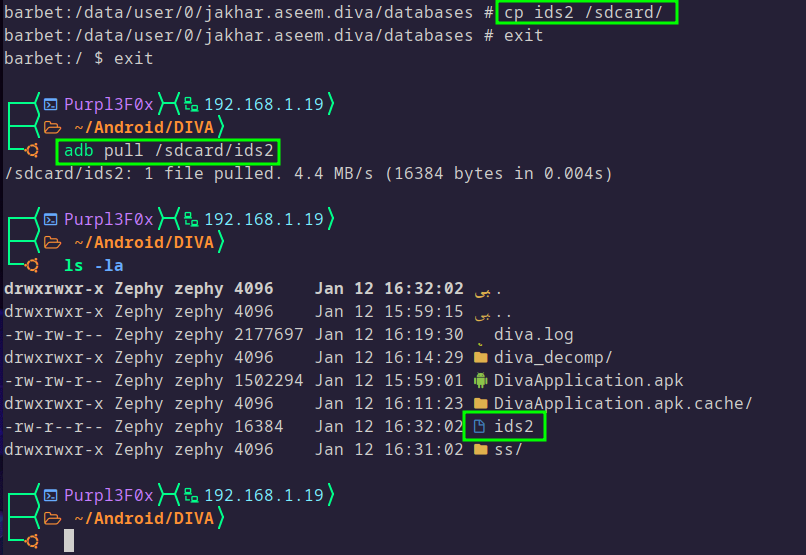

At this point, the method you use to view the contents of the database is up to you. There are tools for reading SQLite databases, you could use Python to read and extract the contents of the database, or use an online viewer:

An amusing side-note; this exercise initially didn’t work for me. I wasn’t sure what was happening, until I realized that the password I supplied, ThisIsn'tSecure, had a single-quote in it, and it was likely causing issues with the SQL statement in the app’s code. In other words, I unintentionally found a SQLi vulnerability!

Insecure Storage 3

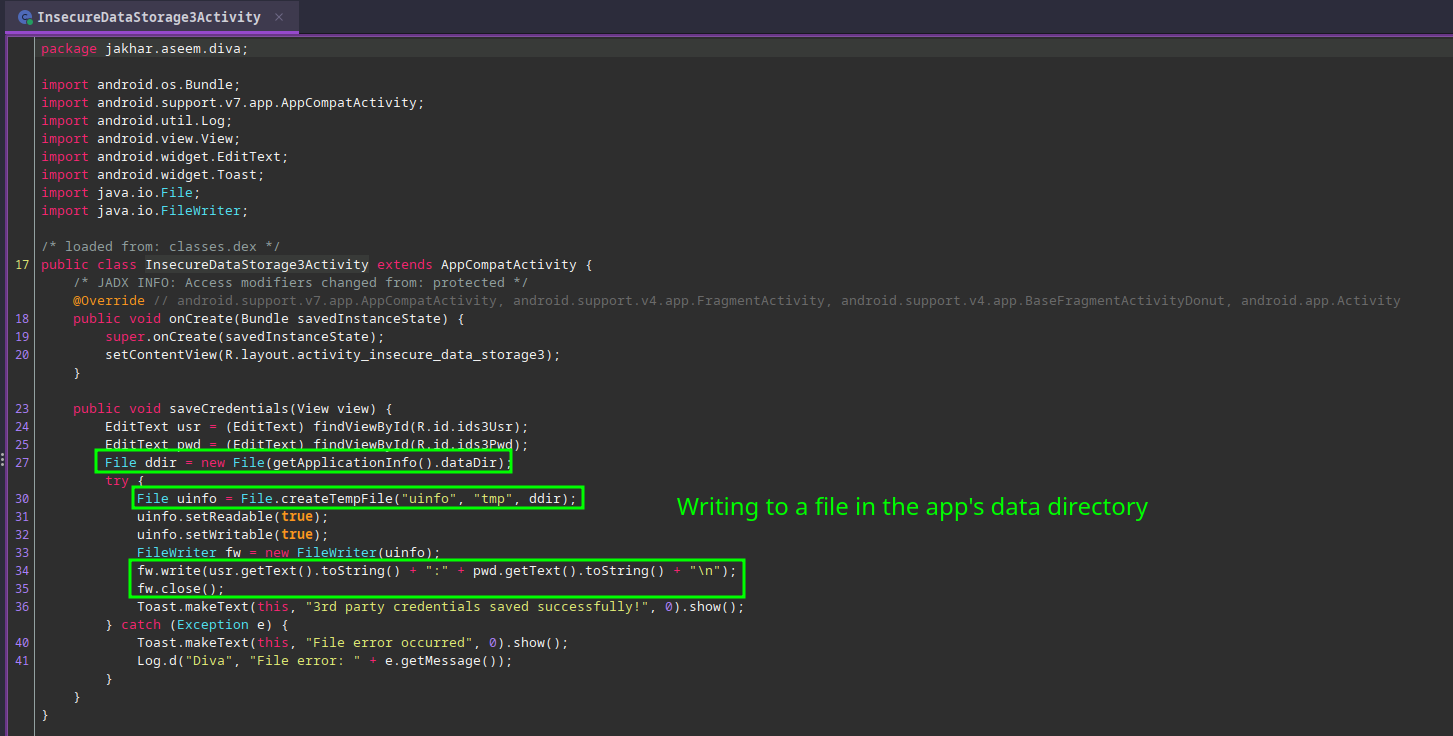

As with the last two challenges, we have to give the app some fake credentials that the app will store somewhere. We’ll go back to Jadx to see what is happening this time:

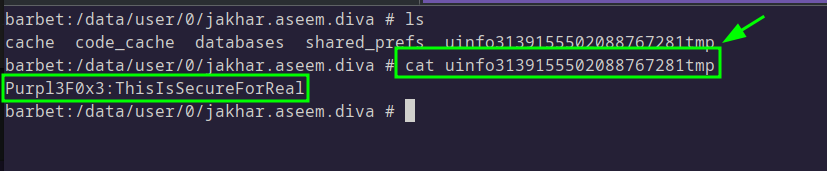

It looks like the credentials are not being hashed or encrypted, and are being written to a file that starts with uinfo. The code suggests that it is being put into the data directory used by the app. This is the same directory that we have already been poking around in:

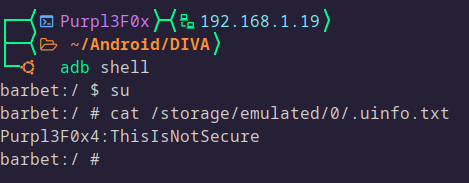

The theory seems to be accurate, and the credentials were found very easily.

Insecure Storage 4

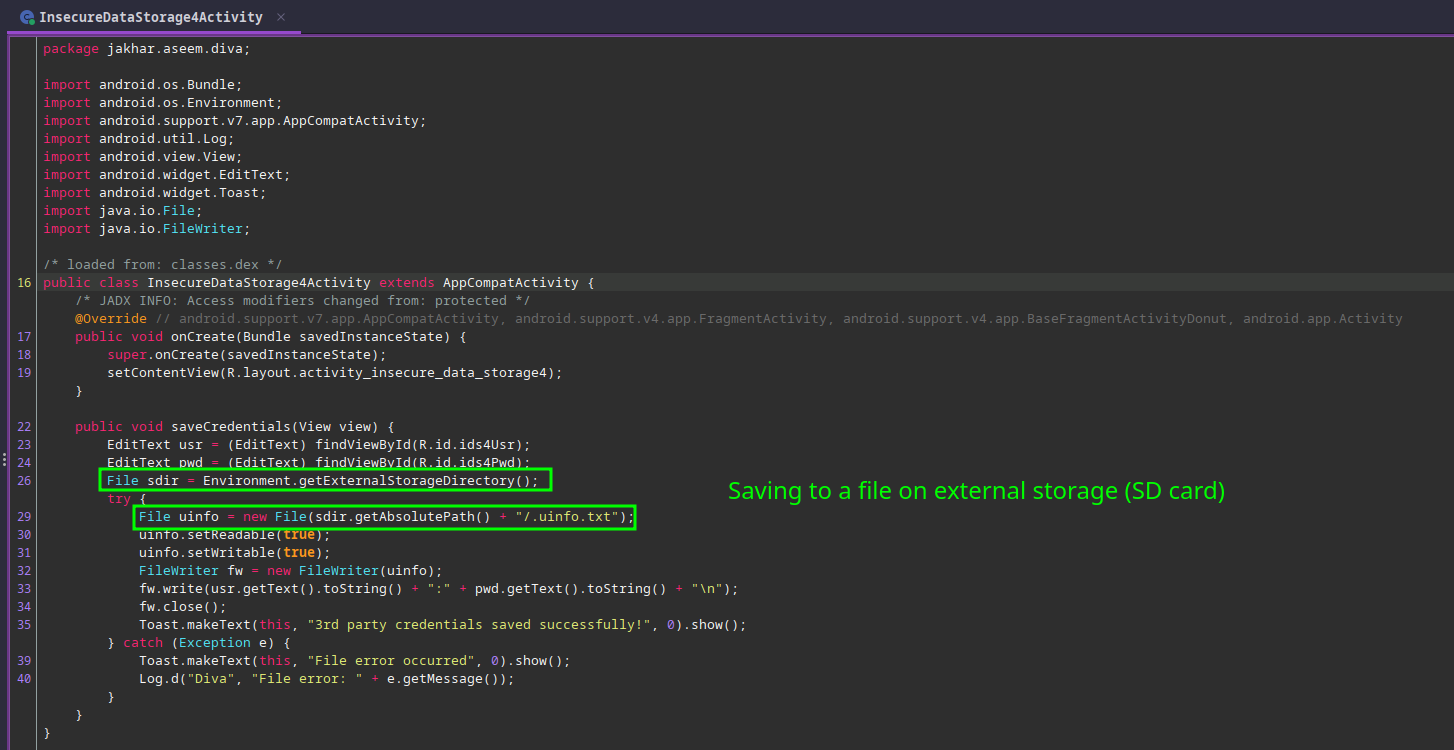

This is the final challenge for the Insecure Storage category, and it was slightly trickier than the others, because the hints from the code were not as straight-forward as I initially thought. Looking in Jadx, it would appear that the credentials are being stored on the SD card:

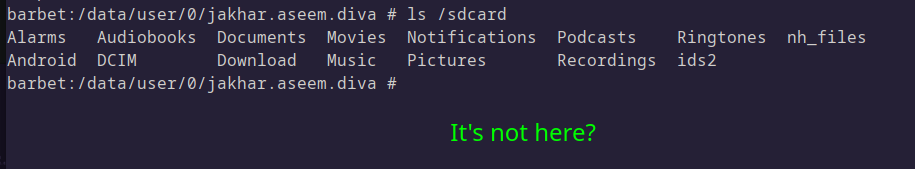

Yet again, there is no attempt to obfuscate the credentials or the file. The app fetches the path to external storage and puts the file there, and yet it doesn’t seem as though the file is in the expected location:

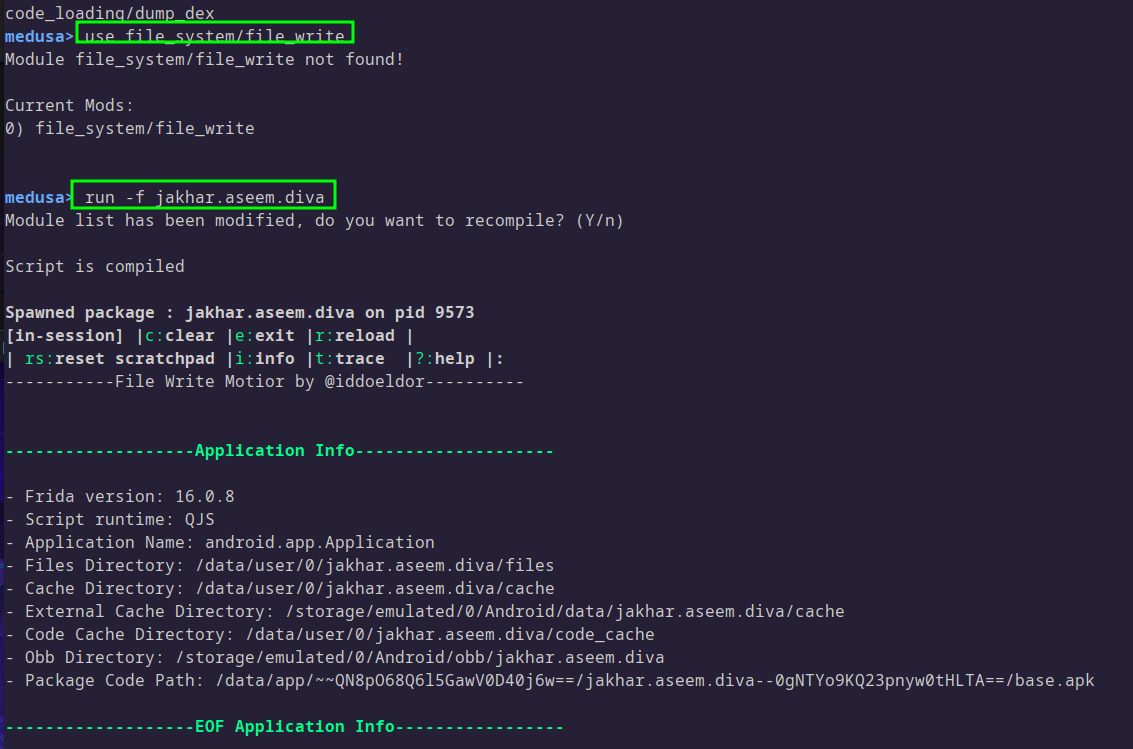

At this point, I was not sure of where to look, so I decided to make use of Medusa to help catch the app in the act of writing the file:

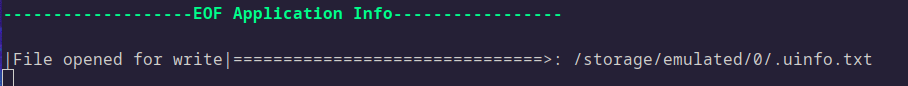

With Medusa hooked into the app, I wrote in some fake credentials again, and this time I was able to determine where the file was being written to:

Conclusion

This concludes the Insecure Storage challenge set in DIVA. Developers have many options when storing credentials locally, but effort needs to be made to do so securely. Credentials should not be stored in locations that are easy to discover, but if there is no way around that, credentials should be hashed using suitable algorithms in order to avoid unintentional disclosure of sensitive data. This is a key area that pentesters should be going over with a fine-tooth comb when conducting security assessments or when participating in bug bounty.

Appendix

Device used:

Tools used:

tags: Pentesting - Reverse Engineering - Android